Dentistry

Victorian Dentistry

Victorian dentistry is a field of study that is as broad as it is deep, so to narrow it down to be more digestible, we are going to use a case study to demonstrate how dentistry was affected by race, class, and gender. This case in particular is about phosphorus jaw, a condition within the world that had a special place within Victorian England's history. While we would like to warn the reader that the condition is rather gruesome, as it has to deal with bone decay, it is an important part of the Victorian Era that can be still felt today. When you light a match in the future, maybe you will have a greater appreciation for the struggles of those in the Victorian era.

Class:

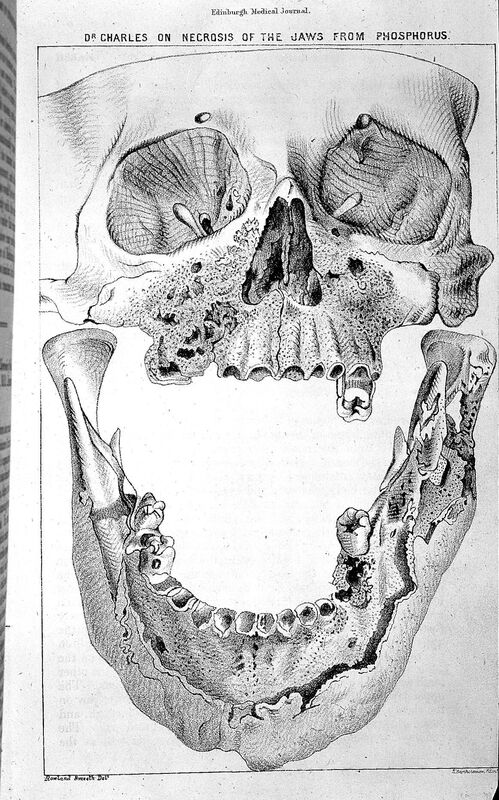

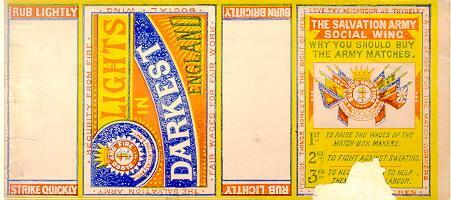

With the introduction of factories and the movement of wealth and prosperity towards cities, jobs were important factors in people's health. In this case, we can use the historical lens to see how a person's dental health could be affected by their class. “Phossy Jaw” or necrosis of the jaw due to phosphorus poisoning, occurs from repeated exposure to white phosphorus. The chemical caused the jaw to break down and necrose. The inhalation of the phosphorus vapors is what caused the condition, it is also why we have red matchsticks today, as red phosphorus is less dangerous than white phosphorus through the invention of a Swedish inventor. They were adopted through the Salvation Army’s factories, the matches were declared to be “Light in the Darkest England”.

Gender

We can use the same case to see how it affected women, as the other term for these people was “matchgirls”. The workers within the factories were typically women so we can state through the lens of gender that the disease was more common in women. The matchgirls were known in the period for staging a strike, at the Bryant and May match factory in London. The action was against the use of white phosphorus, unfair wages, deductions, and hours. The strike was successful and was the start of the Union of Women Matchmakers. This is the social action that inspired the actions of the Salvation Army, that were mentioned above.

Race

Stepping out of the scope of London, several companies had manufacturing plants of white phosphorus in other countries. Due to the strike and revolution of the industry, several companies followed suit in banning the production of white phosphorus matches. The United States banned the matches in 1912, India and Japan banned the production of the matches in 1919, with China banned them in 1925. According to Myers and McGlothlin, “... in 1919 the International Labour Organization's first International Labour Conference established the White Phosphorus Recommendation (Recommendation Number 6), which was an adaptation of the Berne Convention.” Which led to further standards in the industry, which lead to the near eradication of “phossy Jaw”.

References

Admin. “Fact and Fiction.” Wayback Machine. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://web.archive.org/web/20080819012839/http://www.salvationarmy.org.au/SALV/STANDARD/PC_60859.html.

Bartholomew, J. “Skull with Jaw Affected by Phosphorus Poisoning.” Wellcome Collection. Accessed March 18, 2024. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/bg3ss9m5.

Devlin, Hugh. “A Historical Review of ‘Phossy Jaw.’” British Dental Journal 234, no. 11 (June 9, 2023): 825–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-5859-9.

Isaac, Susan. “‘phossy Jaw’ and the Matchgirls: A Nineteenth-Century Industrial Disease.” Royal College of Surgeons, May 13, 2019. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/library-and-publications/library/blog/phossy-jaw-and-the-matchgirls/#:~:text=Phosphorus%20necrosis%20of%20the%20jaw,and%20sometimes%20fatal%20brain%20damage.

Meyers, Melvin L, and James D Mcglothlin. “(PDF) Matchmakers’ ‘Phossy Jaw’ Eradicated.” researchgate. Accessed March 17, 2024. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/14306260_Matchmakers’_phossy_jaw_eradicated.

Ross, Ellen, ed. Slum Travelers : Ladies and London Poverty, 1860-1920. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007. Accessed March 17, 2024. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Satre, Lowell J. “After the Match Girls’ Strike: Bryant and May in the 1890s.” Victorian Studies 26, no. 1 (1982): 7–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3827491.